The Farce of New Coal Mines

Sarah Shibley & Drew Yewchuk

Public Interest Law Clinic, University of Calgary.

Alberta recently rescinded the 1976 Coal Policy. The 1976 Coal Policy consisted mostly of general policy goals government would consider when approving coal projects, although most of these requirements were given little consideration. The one part of the policy that was seriously applied was a land-planning system that divided the province into categories on which coal mining would be generally allowed, generally not allowed, and not allowed.

Is Alberta phasing out Coal?

Alberta committed to ‘phasing out coal’ but with enormous caveats. Alberta only committed to phase out the use of coal-fired electricity generation by 2030. That falls well short of committing to end coal mining. Alberta will continue to mine coal for export, and Alberta still allows coal to be used for steelmaking purposes. There is no plan to stop operating coalmines in Alberta, and based on the rescission of the 1976 Coal Policy, it seems the Alberta Government plans to grow Alberta’s coalmines. That will diversify Alberta’s economy so that instead of being reliant on a single carbon intensive and heavily polluting industry subject to high price volatility, Alberta will be reliant on two carbon intensive and heavily polluting industries subject to high price volatility.

Alberta’s imminent return to coal mining follows the massive development of coalmines in Australia, and Australian mining companies are among the companies at the forefront of the plan to mine Alberta’s coal. Australia embraced the coal industry with such vigour that in 2016 an Australian senate committee ended up writing a report on the re-emergence of black lung disease in coal miners, a disease that Australia thought it had eradicated by 1980.

“Clean coal” is a marketing term used to give the impression coal has become safe and non-toxic, the same strategy that brought us ‘filtered cigarettes’ – the difference is an added illusion of safety.

Faced with the bad press of being known primarily as a source of lung disease, water contamination, and being a major driver of climate change, the coal industry underwent a branding exercise of splitting coal resources into two types: thermal coal, used for heating and power generation, which is generally accepted to be environmentally damaging, and metallurgical coal, which coal companies and trade groups describe as clean, environmentally friendly and necessary for a transition to green energy. Proponents of coal use the term “clean coal” to persuade the public that their activities will be less environmentally harmful than the coal mines of the past. Not only is the definition of “clean coal” unclear, it is misleading about the pollution emitted by the coal. “Clean coal” is a marketing term used to give the impression coal has become safe and non-toxic, the same strategy that brought us ‘filtered cigarettes’ – the difference is an added illusion of safety.

What is the major difference between thermal coal and metallurgical coal? Not much – metallurgical coal generally has fewer impurities and less ash, but there is no universally accepted minimum quality for metallurgical coal. Metallurgical coal is simply the more valuable coal, and there is no clear and commonly accepted standard for what level of coal quality is necessary for metallurgical coal.

Although the proponents of coal are quiet about it, coal is not going to be permanently necessary for steel. Steel can be recycled using electric arc furnaces that only use coal as a power source - meaning that coal can be replaced with any other energy source for steel recycling, which can fill a growing amount of global demand. Electric arc furnaces that can be used to refine raw ore into steel are already under development.

Even for all the bluster about metallurgical coal being so much more important that thermal coal, Alberta has also continued to permit thermal coal mining. Vista Coal Project is a thermal coal facility near Hinton that applied to significantly expand their mine area. Instead of holding a proper environmental assessment, the federal government committed to performing a strategic assessment of thermal coal mining – and only thermal coal, allowing metallurgical coal to avoid scrutiny. The promised strategic assessment for thermal coal has not yet been started.

The Regional Planning Problem

The foothill of the Crowsnest Pass, near the site of the newly proposed Grassy Mountain Project

The Alberta Land Stewardship Act, SA 2009, c A-26.8 (ALSA) was supposed to provide Alberta with landscape level planning and cumulative effects management, by developing regional plans covering the entire province. Almost immediately after the act was passed, amendments were made that kneecapped the act and kept it from being effective. ALSA divided the province into seven regions, each intended to have a regional land management plan. These ALSA plans are presumably the replacement for the land categories in the 1976 Coal Policy. That presents a major problem though: only two of the plans have been completed. The areas facing major coal development run through three regions, and only one of them has a completed regional plan. The one plan that is complete in the coal development area is the South Saskatchewan Regional Plan, and it relies on future subregional or issue-specific strategies to provide a suitable replacement for the 1976 Coal Categories. So Alberta does not have a replacement for the 1976 Coal Policy – it has less than one third of a replacement policy.

The 1976 Coal Policy probably was out of date, but it is obvious a replacement should have been prepared before the policy was rescinded. An out of date policy for long term land planning is better than no policy at all, which is what Alberta has now for most proposed coal mines.

The suggestion that the Alberta Energy Regulator’s licensing process will protect the interests of Albertans is hard to take seriously. The Alberta Energy Regulator is mostly known for their massive failure to control the orphan well problem, the time the former president of the AER misappropriated a couple million dollars of AER money, and their recent decision to suspend environmental monitoring because of COVID, even as the federal government was giving oil and gas companies money to perform other work.

The suggestion that the Alberta Energy Regulator’s licensing process will protect the interests of Albertans is hard to take seriously.

The Mine Security Problem

Coal mines are the classic example of an environmentally damaging industry. Fortunately, Alberta has a program for making sure mines pay for the environmental clean-up and remediation of their mines. The Mine Financial Security Program (MFSP) was established in 2011 and it is administered by the AER. Unfortunately, the MFSP does not work.

The Auditor General of Alberta released a report on the MFSP in 2015. The MFSP uses the asset-to-liability approach for determining the size of the deposits the mining company must pay to the regulators. Readers familiar with Alberta’s orphan oil and gas wells are already familiar with the end result of the asset-to-liability approach. An asset-to-liability approach fails completely when the price of the resource that comes out of the mines or wells drops suddenly. Coal, gas, and oil are all famously price volatile commodities in normal conditions, and the possibility of a major shift to renewable energy raises the possibility of a permanent collapse in prices.

This is the source of the largest problem with the MFSP: if the price of coal drops quickly causing coal mines to become unprofitable and enter bankruptcy, a thing that happens regularly, the MFSP massively fails and the clean-up costs are left to the government. The AER’s calculations from the end of June 2019 estimated the liabilities for clean-up to be around 31 billion dollars, with the MFSP currently holding less than 2 billion dollars in security. The MFSP’s scheme of collecting enough security by hoping resource prices do not seriously drop in the future is like a plan to grow oranges in Fort McMurray by hoping that it never gets cold ever again.

Another problem is that the MFSP lays a financial trap for Alberta. The world must shift to less carbon intensive sources of energy and steel in order to lessen the catastrophic impacts of climate change. The MFSP gambles Alberta’s future on a bet that coal prices will stay high until the Albertan coalmines have already been closed down and remediated, probably a 25-30 year period. By approving coal mines under the current MFSP, Alberta is choosing not to act on climate change now. But it also means that if Alberta later chooses to take any action on climate change that reduces the value of Albertan coal, the MFSP will fail to collect sufficient security and leave Albertans to pay for the clean-up.

A smaller version of this same trap already sprung on Alberta with the limited phase out of coal used for energy: payouts compensating the owners of the coal powered energy generators cost the province around $1.1 billion, and Alberta is facing a NAFTA action by a coal mining company for not being compensated for similar reasons. It is too late for Alberta to be in the driver’s seat for the transition to a greener future, at this point the question is whether Alberta can escape getting run over by the car.

It is too late for Alberta to be in the driver’s seat for the transition to a greener future, at this point the question is whether Alberta can escape getting run over by the car.

The Unsolved Environmental Issues

The environmental damage caused by coalmines has been well-documented since the industrial revolution, but are modern coal mines ‘clean’? Not a chance. Inside Canada, a large coalmine in B.C. has been leaking hazardous amounts of selenium into the Elk river for years, and the mine operator has been unable to get the problem under control. The selenium has poisoned threatened species of trout, and is creating an international problem by poisoning rivers flowing into Montana.

In addition to the ongoing selenium issues at Teck’s mine, the 2013 dyke breach at Obed Mountain Mine provides another example of modern large-scale environmental damage from coalmines. On October 31, 2013, a dyke catastrophically failed and 670 million litres of contaminated water and 90 000 tonnes of sediment and coal fines flowed from the Obed mine into Apetowun Creek and Plante Creek, which flow into the Athabasca river. The wave of sludge killed fish, including the Bull Trout and Rainbow Trout and destroyed several kilometers of their habitat. Downstream communities and livestock producers received water advisories. The impacts of the Obed spill are still being cleaned up, and remediation work will be ongoing until at least 2021.

The Coal Industry’s Long History of Regulatory Evasion

Coal is a bankruptcy industry: massive American coal companies have been regularly entering and exiting bankruptcy since 2015. Why do they keep opening new mines? Because bankruptcy allows them to ditch their liabilities to clean up mine sites and provide health care to their mineworkers. The American coal industry has used bankruptcy law to avoid paying their environmental liabilities, meaning they leave the pollution for the public to deal with while investors walk off with the profits.

Alberta’s oil and gas industry recently attempted the same strategy of using bankruptcy to leave their environmental liabilities to the public, and was most recently stifled by the Supreme Court of Canada in Orphan Well Association v. Grant Thornton Ltd., 2019 SCC 5. That strategy has not yet succeeded in Canada, but resource extraction companies have the cash to try again. The Alberta Energy Regulator has still not fixed their liability management systems in response to the facts that became infamous after the Orphan Well Association case. The Federal government just bailed oil and gas companies out from $1.7 billion of their environmental liabilities. Why would coal companies plan to pay for mine clean-up when they know the government is willing to pay for clean-up once the environmental risks get too out of hand?

Alberta’s Future Coal Mines

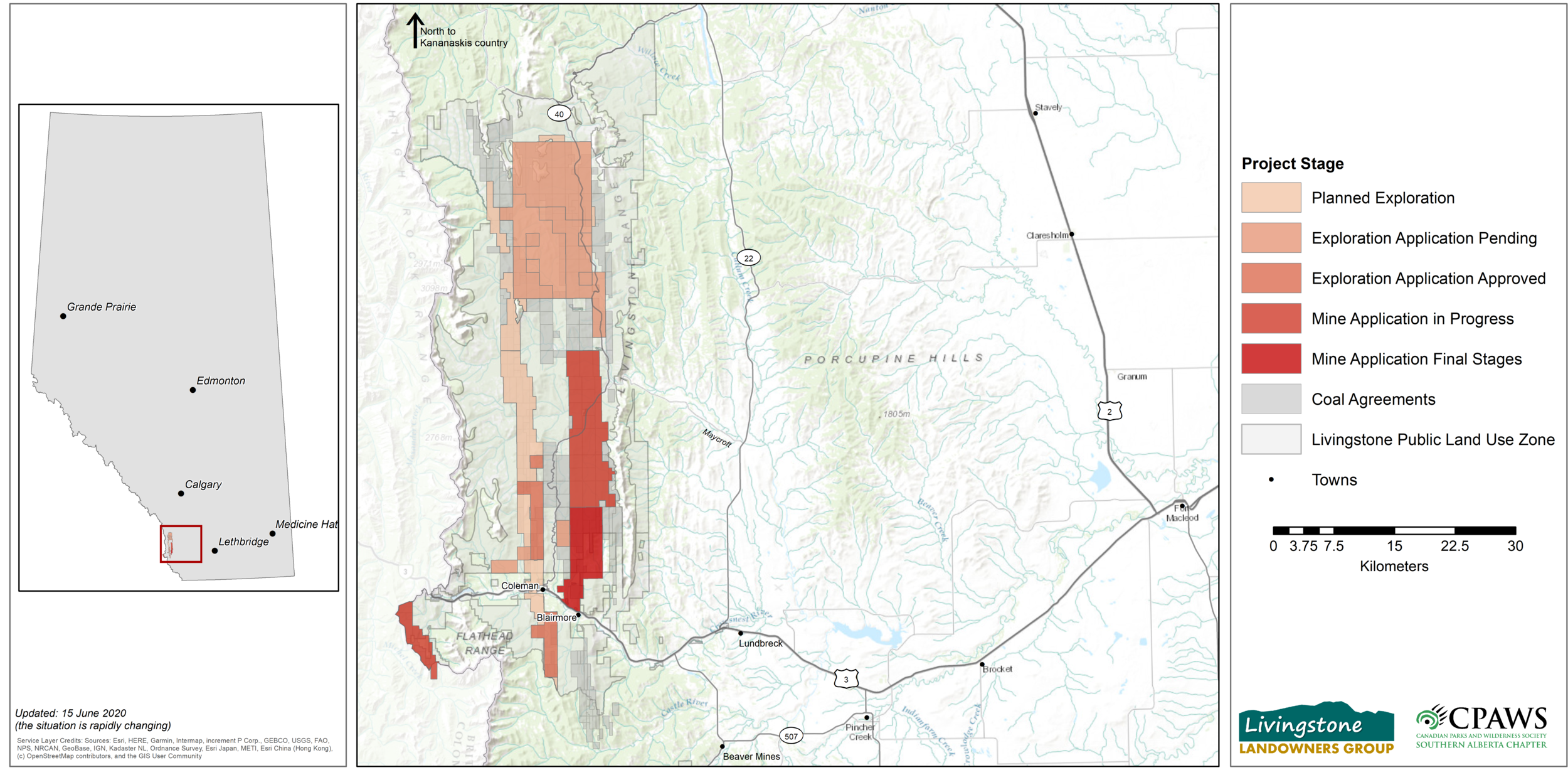

There are a lot of coalmines being planned in Alberta. These include the Grassy Mountain Coal Project, Atrum’s Elan South and Isolation South projects, the Cabin Ridge Project, Tent Mountain Mine, the Chinook project, and the Aries Coal Project. The Grassy Mountain Coal Project, Atrum’s projects, and the Tent Mountain Mine are in the Crowsnest pass region of the Eastern Slopes.

Montem Resources owns both the Tent Mountain Mine and the Chinook Project in the Crowsnest Pass region. The Tent Mountain mine is on the edge of the Castle Wildland Provincial Park. The Chinook Project is located near the town of Coleman. It will produce 4.5Mtpa of Hard Coking Coal and will take the form of an open cut mine.

The Aries Coal Project owned by Ram River Coal is a proposed surface mine projected to run for 30 years if built. The Project is located in the eastern Rocky Mountain Foothills of Central Alberta, 45km west of the Town of Rocky Mountain House, on top of critical habitat for the Bull Trout (see figure 38 of the Proposed Bull Trout Recovery Strategy). The Aries Project is within the North Saskatchewan regional planning zone, for which ALSA planning was initiated in 2014, but the plan does not exist yet.

The proposed Cabin Ridge Project is 16km east of Teck’s Line Creek coal facility in the Elk Valley of British Colombia. The proposed Palisades coal project is located near Hinton, just west of William A. Switzer Provincial Park.

The Grassy Mountain Coal Project, located in the Crowsnest Pass, is the closest to starting production. Grassy Mountain is heading to the hearing stage of their environmental assessment soon. The project is operated by Benga, a wholly owned subsidiary of Riverdale Resources, now owned by the Hancock Prospecting. Hancock Prospecting is controlled by an Australian billionaire with a record of funding climate change denial.

The risks presented by the mine include waste rock leaching toxic quantities of selenium into nearby streams, which causes birth defects and reproductive failure in wildlife. Sensitive species at risk, such as the threatened Westslope Cutthroat Trout are susceptible to this threat. The project proposes to control this problem using experimental mitigation measures (for a detailed analysis, see A. Dennis Lemly, “Environmental Hazard Assessment of Benga Mining’s proposed Grassy Mountain Coal Project” (2019) Environmental Science & Policy, Vol 96).

As discussed above, coal mining around the Elk River, only 30 km away from the proposed Grassy Mountain Coal project site, has contaminated the Elk River with selenium from Canada down into the United States, poisoning Westslope Cutthroat Trout and harming the water quality of indigenous groups on both sides of the border. The government fined the mine operator 1.4 million dollars back in 2017, but the company The mine operator has still not been able to bring the pollution under control. The Grassy Mountain project plans to use similar mitigation techniques despite their resounding failure in British Colombia.

Montems’ and Atrums’ projects add to the risks in the region. While the Elan South project has been described in Atrum’s annual reports, the joint review panel for Grassy has determined that the project will not be considered in the environmental assessment of the Grassy Mountain Coal Project’s cumulative effects.

Costs of Increased Coal Development

The costs of these coal-mining operations are not outweighed by the benefits. While the coal industry claims that the “three projects in the South Saskatchewan /Crowsnest Pass region could generate $3 billion in new government revenues and create over 5000 direct jobs in Phase 1 alone” A. Dennis Lemly puts the likely benefits and costs of future coal mines into perspective for Albertans:

“The aggregate economic impacts of these costs could easily exceed $30 million per year, and deal a devastating blow to the local and regional economy…At an average pay rate of $38 per hour, [which] translates to a total annual employee payout of between $7 and 19$ million…is completely offset by the economic loss resulting from environmental impacts of the project.”

Conclusion

Overall, a wave of new coalmines will benefit mine owners and bankruptcy lawyers, and harm Albertan wildlife, the people of Alberta, and an Earth already getting roasted by climate change. The appropriate replacement for the out-dated 1976 Coal Policy is simple: an outright ban on new coal mines in Alberta – both thermal and metallurgical. The reality of climate change is that coal and oil cannot be growth industries if we are going to have a liveable planet.